Politics in Comics: Uncle Sam

This is part of an occasional series I’m working on covering comic books with strong political content. In honor of Independence Day, I’d like us to take a look at the comic book versions of our national personification, Uncle Sam.

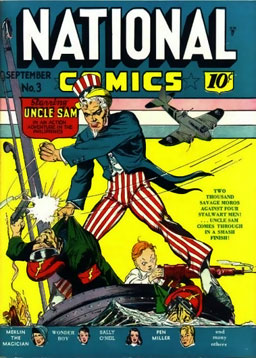

Of course, Uncle Sam, the bearded, top-hatted guy who wants YOU for U.S. Army, had his origins long before comic books (though his appearance was often refined in editorial cartoons in the 1800s). But during World War II, Quality Comics made him a superhero for a few years.

Uncle Sam’s first comic book appearance in 1940

The comic book version of Sam had various mystical powers and helped fight the Nazis ’til his comics were cancelled in 1944. DC Comics bought the rights to the character and revived him a few years later as the leader of a team called the Freedom Fighters. Later, they wrote a new origin for him in which he became the literal Spirit of America, reborn every few years in the body of a dying patriot.

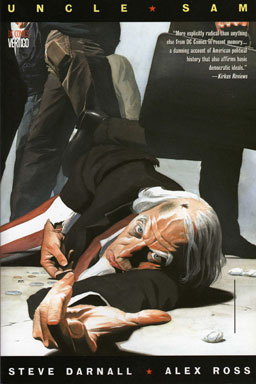

My personal favorite incarnation of Uncle Sam in a comic book is from 1997’s “Uncle Sam,” written by Steve Darnell with art by super-painter and former Lubbockite Alex Ross. It was published by Vertigo Comics, a division within DC for more mature stories. It’s a much darker and less optimistic vision of Uncle Sam and America, but it’s also much more compelling. This is an Uncle Sam for grownups and realists.

The ’97 version of “Uncle Sam”

This one isn’t a superhero, and the story itself isn’t told in a superhero universe. In this comic, Uncle Sam is a deranged homeless man who just thinks he’s the immortal Spirit of America. Either that, or he really is the immortal Spirit of America who’s become paralyzed by guilt and shame over the state of the nation. It’s hard to tell, since he keeps having flashbacks of himself as a Revolutionary War soldier, and he gets into conversations with the national personifications of Great Britain and the Soviet Union.

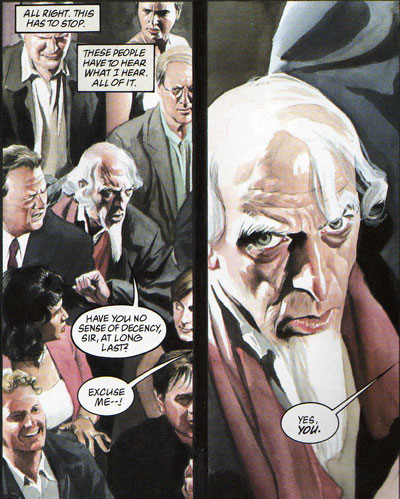

Of course, these may just be hallucinations. It doesn’t seem likely that he’s able to talk to cigar-store Indians and lawn jockeys, or step into paintings, or live through fire, or grow to giant size. But we’re never entirely sure, because Sam’s never entirely sure either.

You should be nicer to your Uncle.

This is, at its heart, a broad examination of America’s history — specifically, the parts of our history (and our present!) that we feel less than proud of. Racism and slavery, the Indian wars, Shay’s Rebellion, Andersonville, Kent State, and far too many massacres and assassinations — the times when Americans have killed, hurt, or oppressed each other because of hate, greed, ideology, or stubbornness.

This is not a comic for the blind, knee-jerk nationalists out there. This is not a book for the “Love it or leave it” crowd. This is not a comic for people who think it’s treasonous to say we aren’t perfect. This is a book that takes a long, hard look at our history, forces us to look at the worst times, and tells us in no uncertain terms that we did wrong, that we failed, that we didn’t live up to the idealistic standards that we should have. Heck, Sam even meets up with a new incarnation of himself who claims to represent “the New America” — a country of media buzzwords, conspicuous wealth (but only for a few), consumerism, hypocrisy, and contempt. And Sam has to confront the question of whether America has changed from the land of freedom, justice, and equality to a nation of far shallower and less noble urges.

If all you want is a book full of marching bands, presidential portraits, and sanitized, whitewashed history… Well, you’re gonna hate this one. You’re gonna think it’s unpatriotic and anti-American. But it isn’t. As far as I’m concerned, a big part of being a patriot is knowing the nation’s history, knowing and accepting the times when we’ve failed to do what’s right, and — most importantly — resolving to do better in the present and the future. A patriot wants his nation to be the best ever, and you can’t move the country forward while keeping your eyes closed.

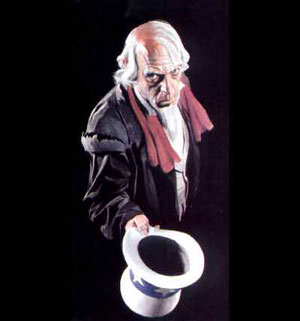

Will work for liberty

You’ll probably hear a lot of people say that this is a liberal comic book, and in a way, it is. But it was written in 1997, when Bill Clinton was president, and Darnell and Ross have said that they wrote it as a commentary on American history and current events. They’ve also said that if they re-wrote it today, they wouldn’t have to change very much of it…

The final message of the story: America isn’t perfect. Heck, it may never have been perfect, not the way we imagined it in elementary school. We’ve made mistakes, sometimes really, really big mistakes over the past 231 years. But we’re better as a nation when we’re trying to live up to the ideals in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. The Powers That Be will snicker and sneer and tell us that freedom and equality are outdated antiques in the modern world, that civil liberties will have to wait ’til we’re not in a crisis, that money is the only real American value. But they’re lying to you, because they’re afraid of the power you hold over them. “Liberty and Justice for All” has always been something worth fighting for. Every version of Uncle Sam would agree.

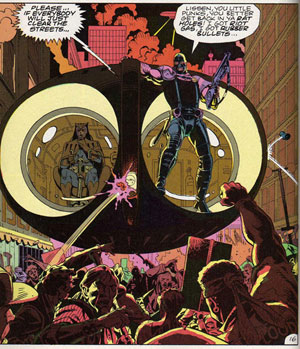

(Previously: Politics in Comics: Watchmen)

Comments off