The Trafficking in Black Lives

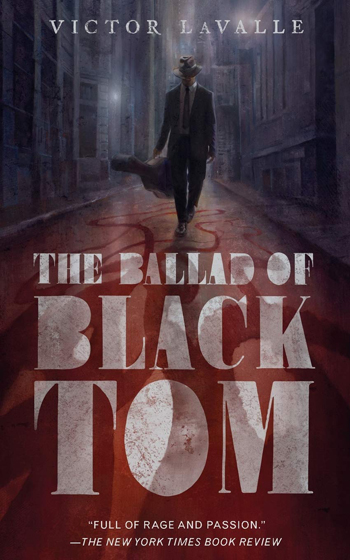

I had some other stuff thought up to review today. And in fact, I’d planned on reviewing this particular book a bit closer to Halloween. But when the time’s right, the time’s right. So we’re going to look at The Ballad of Black Tom by Victor LaValle.

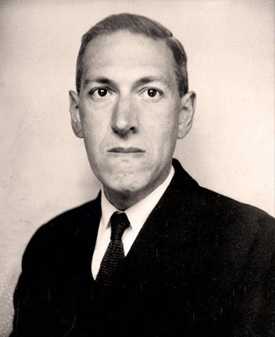

This is a novella written just four years ago, and it’s basically a rewrite of H.P. Lovecraft’s notoriously racist short story “The Horror at Red Hook.” And that means, before we get to LaValle’s book, we’re going to need to talk about Lovecraft, his books, and his legacy first.

It’s the 21st century, and after decades of critical neglect, Lovecraft has become accepted in the last few years as one of the most influential horror and fantasy writers in history. The mainstream critics are a long way behind horror fans, who have been fanatically loyal to Lovecraft’s Cthulhu Mythos almost from the moment HPL died.

Lovecraft’s extensive correspondence with other writers, including Robert E. Howard, Robert Bloch, August Derleth, Clark Ashton Smith, and dozens of others, influenced the development of horror fiction in the first half of the 20th century, and the popularity of the Lovecraft Circle has influenced fans and creators ever since. You will be hard pressed to locate a horror writer who hasn’t been inspired by Lovecraft’s stories — and who hasn’t written his or her own pastiche of his works.

But Lovecraft had some very significant problems of his own that hinder attempts to spread his fandom more broadly — namely, that he was a racist. And not in that “Oh, everyone was racist back then” sort of way that you can kinda ignore. He was a full-on racist, at a level that even his friends thought was much too extreme.

And this wasn’t racism that he kept private — he was very public about his racism, and it showed up prominently in several of his stories. He’d probably always been a bit racist — you might expect it from a sheltered, slightly snobbish man from New England who idolized an archaic British society he hadn’t even been born into.

But that changed in 1924, when Lovecraft got married and moved from Providence, Rhode Island to New York City. He was not very successful at finding work, at least partly because he had a bad attitude about job-hunting and seems to have believed that he was entitled to good jobs, just because he was an educated, quasi-aristocratic white man. But his wife had a successful hat shop and was able to pay all the bills.

But when the shop failed, and she moved out of the city for a job, Lovecraft continued to be unsuccessful at job-hunting. He had very few marketable job skills, and he really felt that as an intellectual and “aged antiquarian” (he was just 34 years old at the time), most jobs were beneath him.

So he had no money and no job, and he lived in the racially mixed Red Hook neighborhood in Brooklyn among black people, Puerto Ricans, Italians, Irish, Polish people — none of them the noble English aristocracy he aspired to be, and all of them managing life better than he was.

So his low-level racism, fueled by his fear of poverty and his resentment of not living his preferred lifestyle, blossomed into high-level racism and bigotry — not merely against African-Americans but against white people he didn’t feel were pure enough.

The direct result of this period of Lovecraft’s life was “The Horror at Red Hook,” which was published in Weird Tales in 1927. This may be the most disliked Lovecraft story — it’s a poorly written story, and even Lovecraft was dismissive of its quality — and the level of xenophobia is absolutely noxious.

Lovecraft’s racism showed itself in other ways, too — the protagonist’s cat in “The Rats in the Walls” is named after a racial epithet, and one chapter of the multi-part “Herbert West, Re-Animator” is devoted to a monstrously racist depiction of a black boxer.

Most significantly, Lovecraft’s racial attitudes became a major theme of his fiction — the fear of horrific sub-humans interbreeding with pure human stock can be seen in “The Shadow Over Innsmouth,” “Arthur Jermyn,” “The Dunwich Horror,” and others.

Ultimately, that may be what makes Lovecraft’s horror tales so powerful. He managed to take his own fears — unfounded though they may have been — and used them to create fiction that has influenced generations of creators and fans.

Nevertheless, even though many fans enjoy Lovecraft’s work — including a not-insignificant percentage of people of color — the depths of Lovecraft’s racism have become more difficult for people to stomach, particularly in a time of increasing diversity. More writers and fans are talking about how to address the fact that the most influential horror writer since Poe has stories you’d be ashamed to show your non-white friends.

And now — finally — we return to LaValle’s novella.

LaValle is an African-American writer who loves Lovecraft’s stories, even knowing that HPL was a racist. In fact, he dedicated the book “To H.P. Lovecraft, with all my conflicted feelings.” As he says in an interview with Dirge Magazine:

He feared non-white people. He feared poor white people. He feared women. He damn sure feared New York City. And yet, to his credit, he actually transferred that sense of horror to the page. He couldn’t filter it out and that’s one of the things that made him great. If I lost that I’d lose the thing that makes him a singular artist.

So rather than completely reject Lovecraft and the Cthulhu Mythos, LaValle decided to subvert it.

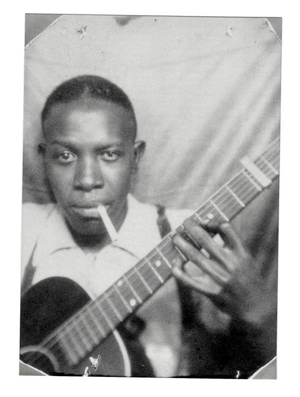

And so in LaValle’s book, we meet Charles Thomas Tester, 20-year-old black man living with his slowly-dying father Otis in an apartment on 144th Street in New York City. Otis is a fantastic musician, but Tommy is really pretty bad. He knows only a few songs on the guitar, and his singing voice is not at all good.

Still, Tommy roams the city wearing a nice but carefully threadbare suit and carrying a guitar case, because black musicians on their way to gigs get less harassment in white parts of town. The guitar case is empty so he can carry illicit merchandise inside — Tommy is a smuggler of unusual artifacts, and he’s been hired to obtain and deliver a small book called The Supreme Alphabet to a rich white woman in Queens called Ma Att. She pays him well for the book, but doesn’t realize that he’s secretly removed the last page of the book to keep her from causing too much magical mischief.

Soon enough, Tommy is on the radar of a wealthy, occult-loving man named Robert Suydam, who invites him to play music at a party he’s giving at his home. Immediately afterwards, he gets acquainted with a corrupt private detective called Mr. Howard and a weak-willed, occult-loving police detective named Thomas Malone, who are tailing Suydam. Otis fears for his son’s life — it’s not smart for a young black man to be seen in certain neighborhoods after dark — but the lure of easy money is too much for Tommy to resist.

He meets Suydam once in his home prior to the gathering and learns some of his host’s occult powers — Suydam shows him visions of the Sleeping King under the sea, which is more than enough to convince Tommy to skip the party the next night.

But when he gets home, he learns that Mr. Howard killed his father while trying to find the last page of the Supreme Alphabet for Ma Att. Alone in a racist society that considers him barely above an animal, Tommy sees no better solution than to return to Suydam and his gospel of overthrowing the world to benefit the downtrodden. But when he learns that Suydam’s guests are the criminal dregs of the world, he realizes that the problem is not a hateful, racist political regime — the problem is mankind itself. And Charles Thomas Tester makes a dangerous, fateful choice.

Days later, Robert Suydam has an army of followers, a new headquarters in Red Hook, and a new lieutenant — Black Tom, a grim black man wearing a natty suit and carrying a bloodstained guitar. But is Black Tom merely the assistant? Or is he calling the shots for something much more terrible than anyone expects?

Verdict: Thumbs up. This book packs a lot of horror in its 150 pages — not just cosmic horror, but the terrors facing black men from Harlem in the 1920s. It changes the Robert Suydam from “The Horror at Red Hook” from a garden variety sorcerer villain to a more three-dimensional — and more pitiful — character. And Det. Thomas Malone, the weirdly poetic and sensitive NYC cop from “Red Hook” stays fairly sensitive but gets to be more active and more interesting.

But the best flip of all — Lovecraft’s most racist story gets a new star, a black man who serves as both hero and villain. We see New York through his eyes, see the violent cops, see the dangers of the subways and the new neighborhoods and the white kids who follow him looking for fights. We see his own prejudices, his friends, the difficulties in finding honest work when everyone is allowed to cheat you. We watch him make the terrible decisions that happen in horror stories — and in the end, you realize that for Tommy, those decisions were actually the right ones.

He ends up as a murderous supernatural destroyer — because why shouldn’t he? When the whole world is against you, is working to grind you down, to destroy your family and friends, whether or not they obey the laws, to disregard you as a worthless, ignorant beast — well, why not just pull the curtain down on the human race? Yes, of course, to the reader, we can think of more socially acceptable solutions. But consider if Lovecraft had written this story — Tommy Tester would’ve been the villain solely because he was a monstrous, deformed, black-skinned cartoon. LaValle gives us a smart, ruthless, terribly powerful African-American man with extreme but logical motives.

Let’s say it one more time for the kids in the back row: When you live in a world that utterly devalues a large segment of the population, that demands absolute subservience from those people, that demands the right to debase them, humiliate them, steal from them, and kill them, punishes them when they defend themselves, and bars them from protesting that abuse, even if done peacefully — and if you then decry them when they take stronger ways to say “NO MORE” — you should strongly consider that you are not the hero of the story, and are very likely to be the inhuman beast at the heart of the tale.

Lovecraft might have deplored LaValle and his story, with its more enlightened view of black people, of New York, of a society geared to crush people just because they have the wrong skin color. I suppose we’ll just have to live with phantom Lovecraft’s disappointment. Because it’s a great story, and you’d love reading it. Go pick it up.

Comments off