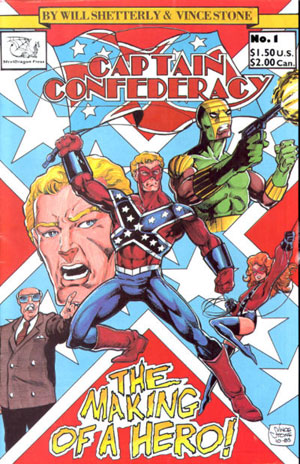

Politics in Comics: Captain Confederacy

I read this comic for the first time not that long ago. It was originally published by SteelDragon Comics, and later by Marvel’s Epic Comics imprint, and it was created by Will Shetterly and Vince Stone. The series ran from the mid-80s to the early-90s. I’d read something about it elsewhere, in which someone assumed, not having read the comic, that it was a pro-Confederacy, pro-racism, pro-Treason-in-Defense-of-Slavery hack job.

It’s not a comic for kids. There’s sex, violence, and a number of very bad and very hurtful words. But I think I can report that it isn’t racist.

Background: The story is set in an alternate history where the South successfully won independence from the North in the Civil War. From there, the rest of North America balkanized into a number of different countries, including the Republic of Texas, Deseret, the Great Spirit Alliance, the People’s Republic of California, and the Louisiana Free State. And in the Confederate States of America, the prime motivator of the Civil War quickly becomes a moot point, as the slaves are freed all over the South. It doesn’t make the CSA a haven of racial harmony, though, as non-whites are second-class citizens. A lot of the bad guys use racist slurs — even some of the heroes use racist slurs.

Which brings us to our main characters — four actors, two white and two black, who are given a super-soldier serum so they can function as a combination of superheroes and propaganda figures for the government. The two white actors become Captain Confederacy and Miss Dixie, defenders of the South, while the two black actors become their opponents, designed to demonize black activists who wanted equal rights. But one of the actors decides to defect to the North, and the government, fearful that their fake superheroes are going to be exposed, brings the hammer down, forcing the actors to decide whether they want to keep pretending to be heroes or go out and become heroes for real…

Shetterly and Stone are reprinting the full comic series in blog form — frankly, their current format is a bit difficult to navigate from within their site, so here are links to the individual chapters.

- Pages 1-20

- Pages 21-40

- Pages 41-60

- Pages 61-80

- Pages 81-100

- Pages 101-120

- Pages 121-140

- Pages 141-157

Again, this is a comic for adults. If you can’t handle sex, violence, extremely bad language, or critiques of racial politics, DO NOT click on those links.

The comic uses a great deal of racist language. But I’ve never believed that racist language alone causes a work of fiction to be racist itself. As a writer, if you’re putting together a story about a deeply racist society, like the CSA in “Captain Confederacy,” if you leave that kind of language out, you make everything look sugar-coated and fake. And this comic, though it has characters who use racist language, comes across as an actively anti-racist book. The villains are people who are working to keep an entire class of people subjugated. The heroes are people who are working to change society for the better. They’re not trying to overthrow the Confederacy, but they are trying to turn it into a vastly less oppressive nation.

As for the story itself, I think of it more as alternate-history science fiction. Altered Civil War settings are one of the more popular styles of alternate-history sci-fi. But you can’t have a story like this without addressing racial issues — sure, they’re somewhat fictionalized, but you can’t live anywhere in the South — heck, anywhere in America — for long before you realize that, no matter how improved we are from decades or centuries past, we ain’t got anywhere near a truly free and racially-equal society. We still got people who think it’s okay to drop the N-word in casual conversation. We still got politicians who’ll kiss up to racist groups for the sake of politics. We still got hardcore racists all over the ‘Net. We still got schoolkids who think nooses are a joke.

There ain’t a comic book in the world that can change that (though comic creators have been trying since Lee and Kirby’s “X-Men #1” in 1963), but it doesn’t hurt at all for comics to try to change what they can.